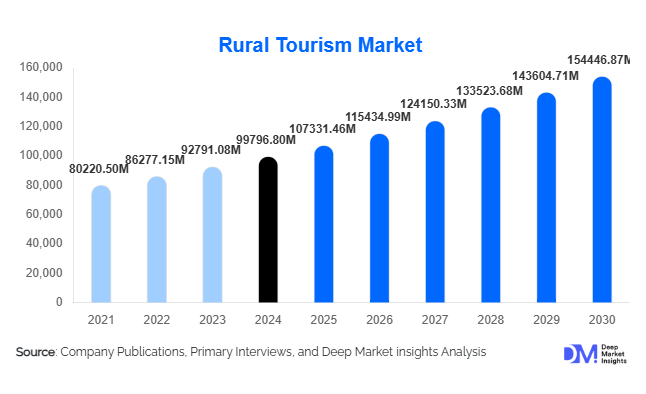

What's Filariasis and Why It Hits Some Folks Hard

Filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by thread-like nematode worms transmitted to humans through the bites of infected mosquitoes. The illness is broadly categorized as a neglected tropical disease because it disproportionately affects low-income regions with limited access to public health infrastructure.

The most widely recognized clinical form is lymphatic filariasis, known for its potential to cause chronic lymphedema and, in severe cases, elephantiasis. Although millions of individuals are infected globally, the severity of symptoms varies significantly. Understanding what filariasis is, how it spreads, and why certain populations experience more pronounced outcomes is central to improving prevention, control, and treatment strategies.

What Filariasis is

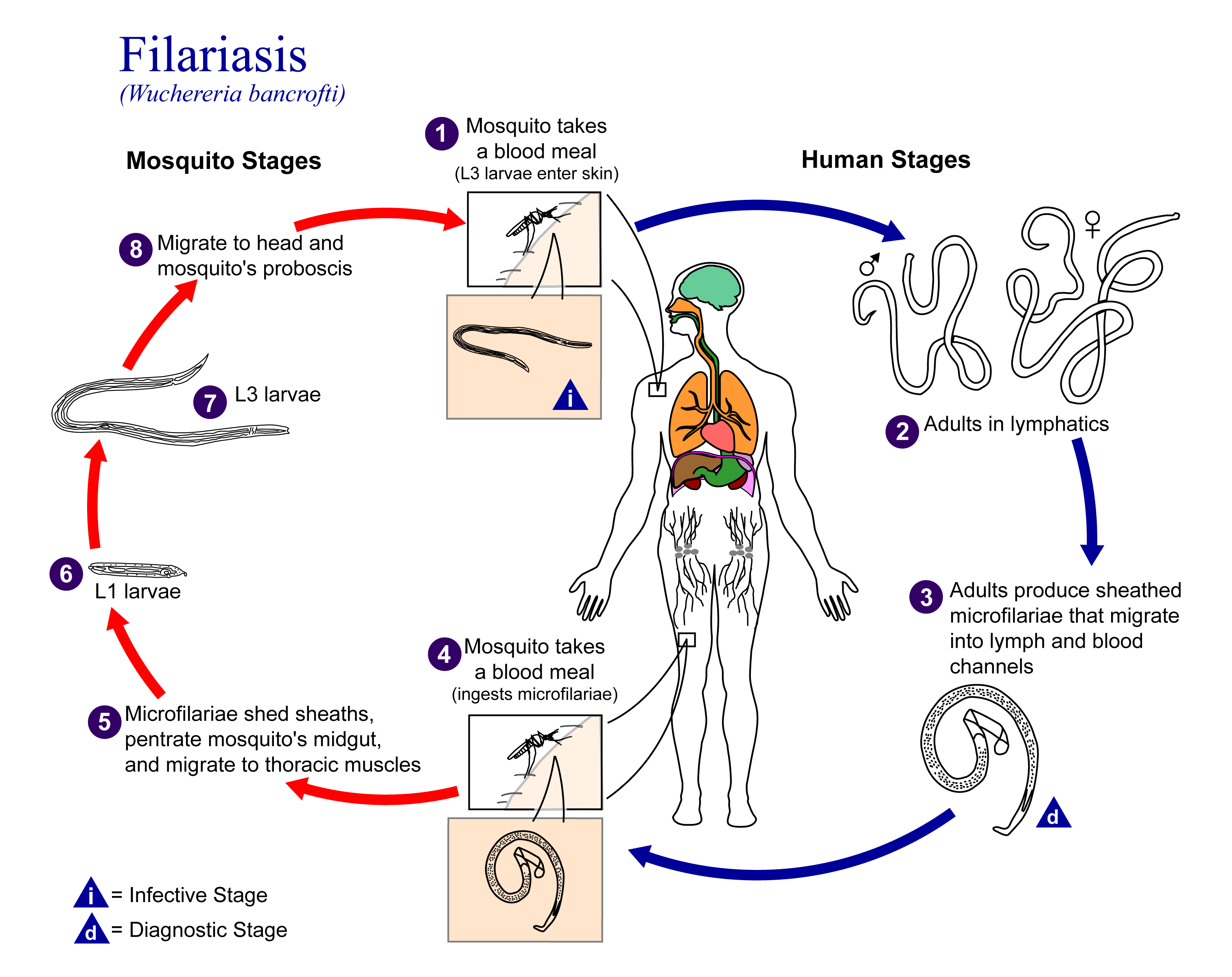

Filariasis results from infection by filarial parasites, most commonly Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. These worms have complex life cycles that depend on human hosts and mosquito vectors. When an infected mosquito feeds on a human, it deposits infective larvae into the skin.

Over several months, the larvae migrate into the lymphatic system, where they mature into adult worms. Over time, the presence of adult worms and the host’s immune response lead to structural and functional impairment of the lymphatic vessels. This disruption underpins many of the hallmark symptoms of the disease. The clinical progression of filariasis can be separated into three general stages:

Asymptomatic Stage

Many infected people harbor microfilariae (the microscopic offspring of adult worms) without experiencing notable symptoms. Despite the absence of clinical signs, the parasites continue to damage the lymphatic system.

Acute Stage

Some individuals develop episodes of acute adenolymphangitis, characterized by fever, chills, swollen lymph nodes, and painful lymphatic inflammation. Secondary bacterial infections commonly exacerbate these attacks.

Chronic Stage

Long-term infection may lead to persistent lymphedema, scrotal swelling (hydrocele), and disfiguring elephantiasis of limbs or genitalia. These chronic outcomes have significant social, psychological, and economic implications.

Although filariasis does not typically cause rapid mortality, the long-term morbidity is profound. Disability, stigma, loss of productivity, and ongoing medical care represent substantial burdens for affected communities.

How Transmission Occurs

Transmission dynamics are shaped by the interaction between the human host, the mosquito vector, and the environment. Multiple mosquito genera including Culex, Anopheles, Aedes, and Mansonia can transmit filarial parasites. Transmission depends on factors such as:

Mosquito density: Higher vector populations increase transmission likelihood.

Climatic conditions: Warm, humid environments allow mosquitos to thrive and support parasite development.

Human behavior: Sleeping without protective nets, working outdoors during peak mosquito activity, and living in densely populated areas elevate exposure risk.

Vector control measures: Regular insecticide spraying, distribution of bed nets, and environmental sanitation reduce transmission but are inconsistent in many high-risk regions.

Why Some People Experience Severe Outcomes

Filariasis does not affect all infected individuals equally. Several factors influence why some people remain asymptomatic while others develop extensive chronic disease:

1. Intensity and Duration of Exposure

Repeated exposure to infected mosquitos increases the cumulative number of larvae introduced into the host. The higher the parasite burden, the greater the likelihood of lymphatic obstruction and chronic damage. Individuals living in hyperendemic regions often rural or peri-urban communities near stagnant water are at the highest risk.

2. Host Immune Response

Variation in immune system function affects how the body reacts to filarial infection. Some individuals develop a tolerance that reduces inflammatory symptoms, while others experience heightened immune responses that lead to inflammatory flare-ups and accelerated tissue damage. Genetic predisposition also plays a role, as certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) profiles correlate with susceptibility to more severe clinical outcomes.

3. Secondary Bacterial Infections

Bacterial skin infections are a major driver of chronic filarial morbidity. When lymphatic drainage is impaired, the skin becomes vulnerable to recurrent infections that worsen swelling and hardening of tissues. Poor hygiene conditions and limited access to basic healthcare increase this risk considerably.

4. Socioeconomic Factors

Limited healthcare access, inadequate sanitation, and poor housing increase exposure to mosquitos and reduce opportunities for early diagnosis. Chronic filariasis is more common among populations lacking resources for vector control, clean water, antibiotics for secondary infections, or routine follow-up visits. Poverty both increases risk and magnifies long-term consequences.

5. Co-existing Medical Conditions

Individuals with malnutrition, chronic inflammatory diseases, or immune-compromising conditions may be more susceptible to symptomatic progression. These factors can alter the body’s defense mechanisms and worsen lymphatic dysfunction.

How Filariasis Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis typically involves laboratory analysis, including

Microscopic detection of microfilariae in blood samples collected at night, when parasites are most active.

Antigen detection tests, which can identify worm antigens even in the absence of circulating microfilariae.

Ultrasound imaging, used to visualize activity of adult worms in lymphatic vessels.

Serologic tests, which detect antibodies but are less definitive for active infection.

Rapid diagnostic tests have become increasingly important in mass drug administration programs due to their simplicity and field utility.

Treatment Approaches

The primary objective of treatment is to lower microfilariae levels within the population to interrupt transmission and prevent the emergence of chronic symptoms. Global elimination programs often rely on annual mass drug administration campaigns. These programs commonly use combinations of antiparasitic medications such as albendazole, ivermectin, and diethylcarbamazine, depending on the region and co-endemic conditions.

In some informational discussions of antiparasitic regimens, references may be made to additional anthelmintic agents such as mebendazole 500mg, though its role in filariasis control is context-dependent and not universally standard. Any medication use must be guided by qualified medical professionals, as regimens differ by region, co-infections, and public-health protocols.

Management of chronic disease focuses on hygiene, skin care, limb elevation, exercise to promote lymph flow, and treatment of bacterial infections. For hydrocele, surgical intervention may be necessary.

Prevention and Control

Because filariasis is preventable, coordinated efforts can reduce disease burden significantly. Key strategies include:

Mosquito control: Environmental cleanup, larviciding, and use of insecticide-treated nets.

Mass drug administration: Community-wide therapy to reduce parasite reservoirs.

Health education: Instruction on hygiene, early symptoms, and mosquito avoidance.

Improved sanitation: Reducing mosquito breeding sites by ensuring proper waste and water management.

Conclusion

Filariasis remains a serious public-health challenge, particularly in regions with constrained resources. Its severity varies widely, influenced by environmental factors, host biology, socioeconomic conditions, and access to healthcare. While the disease is rarely fatal, its chronic manifestations impose significant physical and socioeconomic burdens. Continued investment in vector control, mass drug administration, hygiene programs, and community education is essential for reducing transmission and preventing the debilitating complications associated with long-term infection.